Building Safety-Grade AI

Systems for Mining Operations:

From AI Prototypes to

Operational Trust

What do batteries, AirPods, and gold have in common?

They all start underground, with an operator controlling a machine worth millions of dollars, hundreds of meters below the surface.

Lithium, cobalt, copper, and rare earths are critical components of modern technology. Before they reach factories or global supply chains, operators extract them using complex, high-risk equipment. These machines come with thousands of pages of documentation and strict safety procedures.

In these environments, information systems are not productive tools. They are safety systems. The wrong answer is not a UX failure. It is an operational risk event.

In this blog, we share lessons from building a question-answering system for mining operators and how the real challenges extended far beyond the AI itself.

The Misconception: AI Would Be the Hard Part

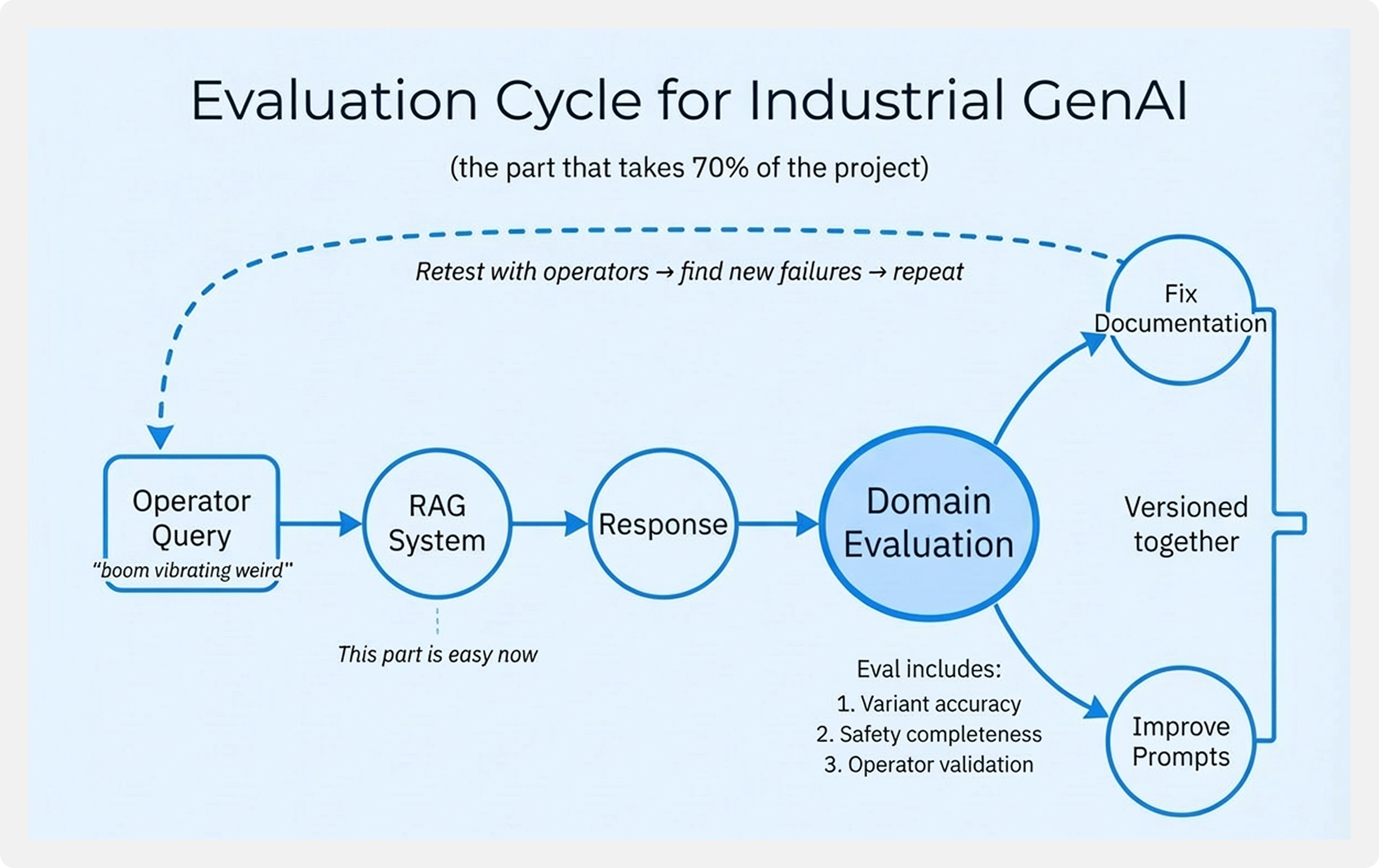

Like many enterprise technology teams, we initially assumed the technical work would be the most difficult part of the project. Designing the retrieval architecture, choosing embedding models, developing chunking strategies, and integrating an LLM felt like the core challenge.

Thanks to mature tooling on Databricks and Azure, we had a working prototype within a week.

What followed was far less glamorous. The real effort involved documenting archaeology, validating safety procedures, and capturing tribal knowledge that existed only in operators’ heads. The AI itself was only a small portion of the work.

This quickly reframed from the project from an AI initiative to an operational reliability and knowledge governance initiative.

A Simple Pitch That Was Far from Simple

The initial pitch sounded straightforward. Operators work with complex machinery; extensive documentation exists, and they need information quickly. The solution appeared obvious: building a decision-support system for safety-critical operations.

On paper, it looked like a tractable engineering problem. Ingest documents, embed them, connect to an LLM, and deploy them.

In practice, it became three distinct challenges: data fragmentation, safety-critical requirements, and user experience. Each demanded fundamentally different approaches and careful enterprise-level attention.

The Three Core Challenges

1. The Data Challenge

Documentation was fragmented across multiple repositories, each owned by different departments. There was no single source of truth. Critical procedures were undocumented, some files were obsolete, and others contradicted one another. No single team had end-to-end visibility, because maintaining it was nobody’s explicit responsibility.

Understanding this landscape required extensive interviews, mapping knowledge sources, and validating information with multiple stakeholders. Before any retrieval code was written, we had to establish what existed, where it lived, and who was accountable for verifying it.

This was not a data engineering problem. It was a governance and accountability problem.

2. The Safety Challenge

In most AI applications, the wrong answer is inconvenient. In mining operations, a wrong answer can lead to injury, equipment damage, or worse. Incorrect torque specifications, incomplete lockout procedures, or instructions for the wrong machine variant are safety hazards, not edge cases.

In this context, AI accuracy becomes a liability issue, not a performance metric.

Evaluation could not rely on standard retrieval scores. Accuracy, completeness, and actionability became non-negotiable. Every response needed to be correct, context-aware, and safe for execution in real-world conditions.

3. The User Experience Challenge

Operators do not type formal questions. Queries often looked like “boom vibrating weird” or “drill overheating after restart.” Early prototypes struggled because they assumed structured, well-formed input.

Real-world testing revealed that the system needed to understand shorthand, incomplete sentences, and language unique to the mining environment. Iterating user experience, informed directly by operator behavior, became central to the project.

Poor UX in safety environments does not cause frustration. It causes unsafe workarounds.

Observing Operators Revealed the Real Need

The client initially asked for a faster search. We asked a simple question: faster than what?

There was no baseline.

By observing operators, the true risks became clear. One flipped through a 600-page manual to find a torque specification. Another called a colleague in a different shaft because their machine variant was not documented. A third made an educated guess because searching took too long.

The enterprise believed the problem was efficient. The real problem was decision reliability under time pressure.

Documentation Was Not a Dataset

We initially treated documentation as a unified input source. It was not. Each department maintained its own files, naming conventions, and versions. Many documents were outdated, some conflicted, and critical knowledge existed only through experience.

Before engineering could proceed, the project became an exercise in institutional discovery. Mapping knowledge ownership and documenting tribal expertise took weeks.

Knowledge fragmentation was not a technical gap. It was an institutional failure mode.

Why Standard Metrics Were Not Enough

Traditional RAG benchmarks measured retrieval consistency, not safety or relevance to a specific machine variant. A high retrieval score did not guarantee a safe or complete answer.

Frameworks like RAGAS could verify whether an answer was grounded in retrieved content, but they could not confirm whether the steps were appropriate, complete, or safe for execution.

We developed a custom evaluation framework across three dimensions: variant accuracy, safety completeness, and operational actionability.

In safety-critical domains, evaluation is a governance function, not a data science function.

Explicit Uncertainty Is a Feature

One of the most important lessons was that confident wrong answers were dangerous. An LLM that admits uncertainty may feel slower, but it is far safer than one that provides a plausible but incorrect response.

We designed the system to surface uncertainty explicitly. Low-confidence answers now reference the exact manual section for verification.

Operators trusted this approach. They were accustomed to uncertainty. What they could not tolerate was false confidence.

Trust in AI systems is built through controlled uncertainty, not artificial confidence.

Enterprise Design Lessons

The project reinforced a fundamental truth about AI in high-risk environments. The technology was the easiest component. Institutional alignment, governance, and operational trust were the real complexity.

In safety-critical industries, AI is not a product feature. It is an institutional infrastructure.